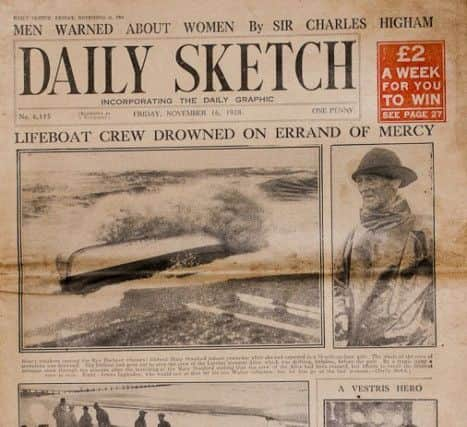

Mary Stanford disaster: Remembering lifeboat tragedy 90 years on

The SS Alice out of the port of Riga, a small Latvian vessel, was in difficulty off the coast of Dungeness.

The weather conditions at the time were among the worst in living memory.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrank Saunders, a launcher on that fateful day, recalled it was a dark and wild morning when they went to assist the launch, blowing a full gale from south, south-east.

The maroon was fired at 5.00am. A member of the crew observed that you couldn’t see across the marsh because of the spray from the water. It wasn’t fog, just the spray from the shallow breaking waters.

It was low water and they had great difficulty in launching the boat – there was a stretch of sand to pull the boat across and it took three attempts before she was afloat.

The crew had to get out of the craft and they were, as a consequence, drenched through before they set off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe had only been afloat a matter of seconds when a message came through recalling the boat as her services were no longer required.

The signalman, Mr Mills, fired his recall flare and Frank Saunders ran across the sands into the water to try to attract the attention of the crew.

The weather was atrocious and they were too occupied in getting the sails set to notice.

The Mary Stanford was a pulling and sailing type lifeboat. She had no engines and no radio – none of the devices that today we regard as commonplace.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith a 15-foot oar in their hands and sails to set in a gale, it is no wonder that they did not see the recall signal.

What happened between setting sail and her capsize we will never know, as all 17 hands on board lost their lives.

Villagers at the time recall the devastating sight of the Vicar, Rev. Harry Newton, kneeling on the beach praying with the women of the village.

Hardly a family in the community of 200 escaped the effect of the tragedy – the worst in British lifeboat history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEventually the bodies were brought back to the Harbour and put in the Fisherman’s Room.

Harry Cutting and young John Head were still missing. All the coffins lay side-by-side with just the words ‘Died Gallantly’ placed on each one.

Ninety years ago, a Sussex Express reporter wrote: “The simple funeral service invested with a solemn dignity, left a memory that shall become a greater memorial to the sacrifice of Rye Harbour, that any monument of stone would ever be.”

The mayor of Rye, Mr Vidler, launched an appeal for monies for the families, which saw donations come in from all corners of the globe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe day of the funeral arrived and it was the biggest known in these parts. There were more than 1,000 wreaths laid. The people attending were so numerous that the service took place in the churchyard.

The crew of the lifeboat had worked together, laughed together and died together, and now they were buried together. The village was in mourning for a very long time having lost so many of their menfolk.

The 17 lifeboatmen who lost their lives were: Herbert Head (47), Coxswain, and two sons James (19) and John (17); Joseph Stonham (43), 2nd Coxswain; Henry Cutting (39), Bowman, and his two brothers Robert (28) and Albert (26); brothers Charles Pope (28) Robert Pope (23) and Alexander

Pope (21); William (27) and Leslie (24) Clark, brothers; Morris (23) and Arthur (25) Downey, cousins; Albert Smith (44); Walter Igglesden (38); and Charles Southerden (22).